ORPHAN SCROLL

1,564 SACRED TORAH SCROLLS – RABBI ZOË KLEIN

In 1942, curators in the Central Jewish Museum in Prague, working under desperate conditions, sent out a call to the Jews in the regions of Bohemia and Moravia, Czechoslovakia, to send their Judaica and artifacts to the museum for safe keeping.The community who sent these items to the museum must have hoped that the treasures would be protected and one day be returned to their original homes.The curators, however, “must have suspected that they were inheriting the legacy of the dead…their work became an act of spiritual resistance.”[i] They thought they were saving Judaism by saving the scrolls from plunder and destruction.

Under Nazi supervision, collating under near impossible conditions, everything was catalogued meticulously. Every scroll was labelled in Czech and German, giving the name of the community and congregation from which it came. All of the museum’s curators and cataloguers were eventually transported to Terezin and Auschwitz, with only one survivor. After the defeat of the Nazis, the scrolls remained in the disused Michle Synagogue, near Prague, for twenty years, until the communists, desperate for money, stumbled across them. The scrolls were not theirs to sell, but that hardly mattered. A philanthropist, Ralph Yablon, brought them to London. Some were damaged by fire, water, nibbled by rodents, rotten, torn – a grim testimony to the fate of the people who had once prayed with them. Inside one was a note: “Please God help us in these troubled times.”

Of the 1,564 scrolls, 216 lost their tags somewhere along their way, and cannot be traced to any community. They became known as orphan scrolls.

OUR LITTLEST TORAH IS AN ORPHAN SCROLL.

There were opposing opinions about what to do with the Torahs. Some believed that the damaged scrolls should be buried. Some believed that the scrolls should be used as memorials to the communities that perished. It was decided that the Torahs should be given to congregations around the world, on long term loan, so that they may be part of living communities.

IN 1976 RABBI GAN AND THE CONFIRMATION CLASS ACQUIRED A CZECH TORAH.

On the fiftieth anniversary of the arrival of the Czech scrolls, there was a reunion of Torahs at Westminster Synagogue. Torahs came from all around the world. Some were transported in golf bags. Some came by Fed Ex Courrier. Canada Air gave two Torahs free seats in First Class. One actually arrived in the back of a limo by itself. My daughter Kinneret and I carried our Torah in a baby blanket, covered in hearts.

I wasn’t very impressed with our scroll. I was, I hate to say it, disappointed in it. When other people opened their Czech Torahs, wow, some of them were beautiful beyond belief, the clarity and artistry of the letters, the flourishes, the ink as bright as patent leather. The columns of text, perfectly straight. Our scroll? Not so much. The columns not straight, lines of Hebrew spilling into the margins, letters kind of blotchy at times, faded, scribbled, sloppy. It made me wonder about the scribe who wrote it. Was he not a good scribe? Was he half blind? Was he a heavy wine-drinker? It was also an orphan scroll, so I was a bit jealous of other communities who knew the towns from where their scrolls came. Some synagogues had even taken trips to visit those towns. I heard about survivors who sought out the scrolls from their villages and prayed and cried over the same Torah over which their parents’ marriage had been blessed.

BUT OURS HAD LOST ITS TAG. OURS IS AN ORPHAN.

There was a scribe there who specialized in the Czech Torahs and I asked him if he could look at ours. Instead, he said, “You know that your Torah is around 200 years old.” I did not know that. He also said, “You know that this is what we call a ‘Unity Scroll,’ because it has both Sephardic and Ashkenazic letters.” What that means is that it may trace its influence all the way back to the rabbis who emigrated from Spain, fleeing the Inquisition. Those rabbis settled in Tzfat, which became the center of Jewish Mysticism in the 1500s. Earthquake led many of them to then move to Fez, and Cordova, Venice and Prague, Prague being the last real center of Kabbalah. Those Spanish/Sephardic letters traveling with them deep into Ashkenazic territory. It may be that it traces its influence to the Great Maharal, Rabbi Judah Lowe, of Prague, who died in 1609, the great kabbalist who, according to legend, brought a Golem to life. Whoever wrote this scroll was a student of the art of both Sephardic and Ashkenazic lettering. He was a mystic.

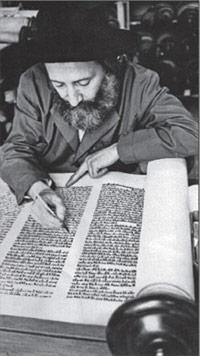

Maybe it was written by a scribe at the end of his career. Maybe it was written by one and finished by another. Maybe a seasoned scribe was training his grandson to write. All Torah scribes are master craftsmen. They are devout Jews. They do not take their work lightly. A Torah takes a year to write. Imagine, a year in the life of the Jewish community in Czechoslovakia, 200 years ago. Imagine the conditions. Imagine how many times were they threatened with pogroms, how many times did this scribe have to hurriedly gather up his parchment, ink and quills and hide.

SUDDENLY OUR LITTLE TORAH BECAME THE MOST PRECIOUS SCROLL IN THE WORLD TO ME.

Its scratched and stains, faded chunky letters, and ungraceful lines, all part of its incredible story. Its age spots and wrinkles and puckers, all clues in a great mystery, all evidence of having lived and been loved, deeply. What would our little orphan scroll tell us, who heralds from not one, but all destroyed congregations? What would our little Torah say about racism, about fear, about hate? And what mystical secrets are hidden in its letters, in this unity scroll, about exile and tradition and survival and hope?

It would say:

My first letter is beit and my last letter is lamed, and I am framed by ‘heart.’ I have been held in your arms and the arms of your parents and great grandparents for two hundred years. I am the voice of Sinai. I am the DNA of history. I am the hard consonants brought to life by the soft vowels of your breath. Together, we are a tree of life. I am the light of the Eternal. I am witness to the glory of God. I am witness to the worst and best humanity has to offer. When there are no more human witnesses, I will remain.

I am the harbinger of peace. I have survived, to challenge us to confront prejudice and hatred. To challenge us to come together, right, left, conservative, liberal, religious, secular, in support of world Jewry, in support of our brothers and sisters in Israel, in support of voices who speak up against atrocities against anyone. I have survived to challenge us to find the image of God in the other, to forgive, to make our people’s suffering meaningful by working, in the name of our millions of martyrs, for a more just and tolerant world, for goodness to prevail, for righteousness to flow like a mighty stream. I am witness. I survived to promote education, literacy, to celebrate the questioning of the young, and the wisdom of the aged. I am here, hineini, to remind you that you are part of a people who challenged God to save strangers in Sodom and Gomorrah, who overthrew the slave system in Egypt, who crossed the Sea of Reeds singing the song of freedom. You are part of a people who followed a pillar of fire across the desert, who stood at the mountain, who heard the shofar blast, you are a holy people, a nation of priests.

I contain 304,805 letters, 248 columns, 84 pieces of parchment, and I’m over 98 feet long.

I am the heart of Jewish life and ethics. My great teaching applies to all human beings, from the Ten Commandments to the commandment to love thy neighbor as thyself. I have given the world Sabbath, and the Exodus, the inspiration behind nearly every revolution against bondage.

The men, women and children who once held me and spoke blessings over me and carried me, most of them were sent to their deaths, their synagogues and communities destroyed. But the holy scroll survived, and remains dynamic, in this living and thriving community, to inspire us into action, to build bridges with our neighbors near and far, to speak up for and protect our people, to speak up for and protect all people, and to commit to a life of goodness, taking pride in our phenomenal history, participating in this remarkable moment in our history, caring for the environment, caring for each other, partnering with our Creator in the ongoing creation of the world.

May our lives be framed by ‘heart,’ filled with a love of Torah, woven together into a unity scroll, facing our future with courage, with joy, with hope.